April 21, 2004

By MARGO JEFFERSON

A Wry Outsider Determined to Endure, Against the Odds

A Wry Outsider Determined to Endure, Against the Odds

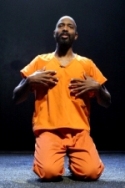

The stage is a rectangle of camel-colored sand. A man stands before us in an orange cotton uniform, standard issue for prison inmates in the United States. But his voice, melodic yet percussive like a vibraphone, marks him as a foreigner.

This man is not an invention. He is a re-creation, a composite figure. The Ugandan-American photographer Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine has interviewed and photographed Ugandans for 18 years to document how they have endured, even prevailed in the face of war and AIDS. "Biro," his first play, opened on Sunday night at LuEsther Hall of the Public Theater and runs through May 9. It is an eloquent, intimate solo piece.

Biro says he came to the United States to get medicine for himself and money for his son's care. He had other expectations, naturally. In Uganda he was a poor young man who had watched friends just back from the United States flaunt their prosperity.

So expectations were like I am crossing the poverty line

When I get to the States I get my education

Moneys from the branches of trees

I'll get my treatment

And in two years having made enough cash I'll go back home

Start a small business

Take care of my son

Eh.

Biro is wry, and a bit defensive, too; the memory stings. And that "Eh" is really an "Ennhhhh," a form of verbal punctuation that means all sorts of things from resolve to surprise, rue to furious despair.

Some solo pieces get bogged down in the past tense; audiences stop believing that conflicts are being lived out in front of them. Mr. Mwine and his director, Peter DuBois, let momentum build, then slow down so that emotions can coalesce. But there are no static set pieces. Biro is trying to figure out his life as he explains it, and he is trying to figure out his relationship to us. He is an illegal immigrant after all. Many of us take the privileges of citizenship for granted.

So he must explain how he was arrested in Texas and put in prison. He was living with strangers, working three jobs, drinking too much some nights because "alcohol cracks the loneliness." He went to a bar to watch Mike Tyson fight and joined a fight his friend Donnell picked with a stranger. When Donnell disappeared, he found himself arguing with policemen.

The trouble got worse. The police said that one of his employers has accused him of stealing money. He did not steal the money but the I.N.S. soon found out that he had a fake Social Security card. Now he is facing deportation. To go back to Uganda now, Biro says, is "as good as a death sentence."

So he goes back to his youth there instead. An Edenic landscape appears on the wall behind him. How could such beauty contain so much grief and terror? Biro was born in 1964; two generations of his family fought the murderous regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote. (Amin was a madman and a nightmare, he says. "But when Obote maneuvered his way back to power in 1980/He quietly killed twice as many people in half the time.")

At 16 Biro ran off to join the army. It was a jumble: battle drills, eclectic political studies, the suffering of malnourished soldiers, the excitement of liberating villages. Mr. Mwine is such an agile, mercurial actor. His long skinny limbs snap into position, and his voice mutates: he's a cheeky enlistee and an earnest revolutionary; he's a big bodyguard named Suicide who talks as if he ate pebbles for breakfast. (When he reaches Texas, his Southern accents, black and white, are perfect, too.)

Heroes who liberate towns and villages drink, party and sleep with every available woman. Sexually transmitted diseases are rampant: "Eh, it was those S.T.D.'s that were popular" in Biro's wry words. Some kind of medicine was brought in eventually.

Biro and a group of soldiers were sent to Cuba in 1986 for military training. As he tells it, nasty geopolitical deals in arms and medical supplies had been made.

After routine blood tests in Cuba, 32 Ugandans were hospitalized and sent back home. Mr. Mwine assumes the officious voice of Uganda's president as he addresses the quarantined men. Fidel Castro has accused him of deliberately sending sick people to a foreign mission. He is aggrieved. He blares:

You have all been returned and as you may be aware

According to Cuban records you have all been diagnosed with H.I.V.

H.I.V. is the disease which causes AIDS and AIDS is incurable

And here you are

But don't get alarmed

Any questions?

By this time we know Biro well. Each detail of his life matters. The 2 sisters who help him; the 10 siblings who don't. His longing for a child because: "I could not believe that when you die you just fly to heaven/In Africa your only life after death is your child." We follow the map of his life and the map of AIDS, across three worlds. And when "Biro" ends, we know we are facing terra incognita.

BIRO

Written and performed by Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine; directed by Peter DuBois; directorial consultant, Mr. Mwine; sets by Riccardo Hernández; lighting by Chad McArver; sound by Acme Sound Partners; projection design, Peter Nigrini; production stage manager, Damon W. Arrington; managing director, Michael Hurst; associate producers, Mr. DuBois and Steven Tabakin; director of production, Joe Levy. Presented by the Public Theater, George C. Wolfe, producer; Mara Manus, executive director. At LuEsther Hall in the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, East Village.

A Wry Outsider Determined to Endure, Against the Odds

A Wry Outsider Determined to Endure, Against the Odds